It is a common misconception that collecting is solely about acquisition or accumulation, for many, the journey of discovery and snapshot of history is fundamental to the hobby. Whether the item in question has been roughly hewn from household silver to fund a city's defence or meticulously crafted in glorious colour to celebrate a state visit, they tell the story of the moments which shape the world around us. The upcoming David Holl Collection of Great Britain has many such items, including lots 168 and 169 from the first and second Indian Round Table Conferences, a short but complex period during the Empire's Colonial Rule of the Country.

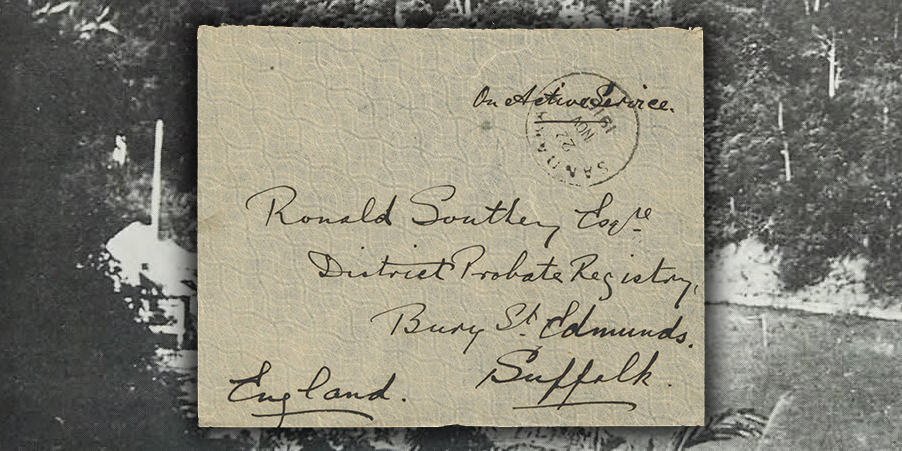

The first Round Table Conference from which Lot 168, St James's Palace stationery sheet bearing a ½d, 1d, 1½d & 2½d emerged, convened in London in November 1930, heralded as an unprecedented effort to shape India's transition to self-governance. It was initiated after the Simon Commission's earlier recommendations, which had been met with widespread protests in India. The conference brought together British politicians, Indian leaders, and princely state representatives, tasked with envisioning a new constitutional framework.

However, this ambitious dialogue was marred by absences. Mahatma Gandhi, leader of the Indian National Congress (INC) and a symbol of the independence movement, was notably absent. At the time, he was imprisoned alongside nearly 90,000 fellow activists following the Salt March and the broader Civil Disobedience Movement. Their protest against colonial rule reflected deep dissatisfaction with British governance, making the absence of Congress a significant limitation for the conference.

Winston Churchill, then a prominent Conservative voice, was another figure critical of the proceedings. Churchill and other conservatives opposed concessions to India, reflecting divisions within British politics that would complicate negotiations throughout the Round Tables.

The tide shifted with the Gandhi-Irwin Pact in March 1931. This agreement temporarily halted civil disobedience, released political prisoners, and paved the way for Gandhi to attend the Second Round Table Conference later that year. Yet, Gandhi entered the talks with clear reservations, famously declaring:

“Negotiation has its purpose and has its play, but only under certain conditions. Without those conditions, negotiations are a fruitless task.”

His skepticism stemmed from persistent disparities in British and Indian objectives. For Gandhi and the INC, independence was non-negotiable. For the British, maintaining control—even under a façade of shared governance—remained a priority.

The Second Conference from which Lot 169 traces it's origin saw Gandhi emerge as the sole representative of the INC, highlighting divisions among Indian political factions. He insisted on addressing issues of caste inequality, particularly the plight of the "untouchables," or Dalits, whom he termed "Harijans" (children of God). His unwavering focus on this cause led to friction with other delegates, including Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who championed separate electorates for Dalits—a proposal Gandhi opposed, fearing it would fragment Indian society further.

While Gandhi sought equity and unity within India, the British faced their own crises. The global economic depression had taken its toll, forcing Britain off the gold standard in 1931. The collapse of the Labour government and the formation of a Conservative-dominated coalition added political instability to economic hardship.

Meanwhile, Indian politics were equally fractious. The negotiations coincided with rising communal tensions, debates over federalism, and demands from princely states seeking to safeguard their autonomy. These issues were compounded by unresolved disputes over representation, particularly the allocation of seats in a proposed legislature. The Poona Pact of 1932, which resulted from Gandhi's hunger strike against separate electorates for Dalits, underscored the complexity of these internal challenges.

By the time the Third Round Table Conference convened in late 1932, hope for meaningful progress had dimmed. Key Indian leaders, including Gandhi and the INC, did not attend, rendering the conference a largely symbolic exercise. Without substantial representation or agreement, the Round Tables failed to deliver a comprehensive solution to India's governance.

In their wake, the British government unilaterally moved forward with the Government of India Act of 1935. This legislation, while falling short of full independence, introduced significant reforms. It expanded provincial autonomy, enfranchised a broader segment of the population, and established a federal structure that laid the groundwork for later constitutional developments. Yet, for many Indians, these concessions were too little, too late.

The Indian Round Table Conferences stand as a testament to the complexities of negotiation under colonial rule. For Gandhi, they underscored the futility of dialogue without genuine intent and equitable conditions. His resistance to compromise on fundamental principles, such as caste equality and self-determination, reflected the moral clarity that defined his leadership.

From a broader perspective, the conferences illustrate the tensions between empire and emerging nations and as Gandhi’s words remind us, meaningful progress requires not only dialogue but also the right conditions for change.

To find out more about the items which emerged from these events, visit www.sgbaldwins.com or register to bid here