A stunning 1529 Gold Dukat will be auctioned later this month, minted by the city in a desperate effort to hold back the heavily armed and battle-hardened Ottoman forces.

The Siege of Vienna in 1529 marked a pivotal moment in European history, representing the first major attempt by the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to capture Vienna, the heart of the Habsburg Monarchy. This battle between the forces of Christendom and the mighty Ottoman Empire not only tested the resolve of Europe but also demonstrated the military might of the Ottomans. The siege had far-reaching implications for the political and religious landscape of Europe, as it was seen as part of a larger conflict between the Christian West and the Muslim East.

Background: Ottoman Ambitions and European Concerns

By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire had reached the height of its power under Suleiman the Magnificent. Suleiman had expanded his empire across the Balkans and North Africa, and his forces seemed unstoppable after their decisive victory at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, where the Kingdom of Hungary was defeated, and its ruler, King Louis II, was killed. This victory paved the way for Ottoman influence in Central Europe. After consolidating their hold on Hungary, the Ottomans turned their attention to Vienna, the gateway to Western Europe, and a strategic stronghold of the Holy Roman Empire under Emperor Charles V.

Suleiman’s ambition was not just territorial expansion but also a show of dominance over Europe’s Christian rulers. Vienna’s symbolic importance as a centre of the Habsburg Monarchy made it a prime target. By taking Vienna, the Ottomans could open a path into the heart of Europe, potentially challenging Habsburg control over the continent and spreading Islamic influence further west

The Siege Begins

Suleiman set out with a massive army, estimated to number over 100,000 men, consisting of highly trained Janissaries, cavalry, and artillery. The Ottoman forces were known for their use of advanced siege techniques, including heavy cannons capable of breaching fortress walls. In contrast, Vienna’s defenders were vastly outnumbered. The city had only around 20,000 men, including a mix of local militias, professional soldiers, and mercenaries hired by the Holy Roman Emperor. The commander of the city’s defence was , an experienced military leader who played a crucial role in organising Vienna’s defences.

Vienna’s fortifications, while strong, were not designed to withstand the full might of the Ottoman siege forces. The defenders worked tirelessly to reinforce the walls and prepare for the onslaught, using every available resource to strengthen their position.

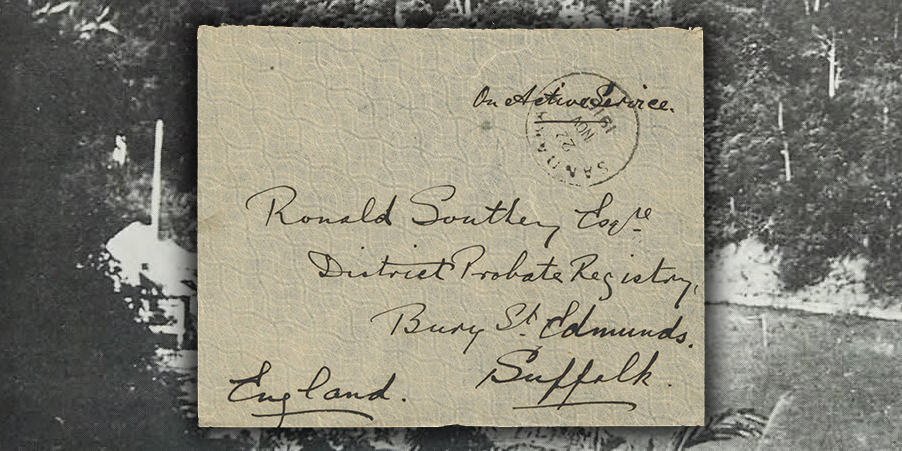

The Emergency Coinage: Treasures of Vienna's Churches

One of the most striking aspects of Vienna’s defence was the desperate measures taken to finance the defence effort. The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, had provided a significant contingent of mercenaries to bolster the city’s defences, but paying these soldiers posed a serious challenge. As the siege dragged on and resources became scarce, Vienna’s leaders resorted to using the treasures of the city’s churches to mint emergency coins.

Gold and silver religious artefacts, many of which had been housed in Vienna’s churches for centuries, were melted down and struck into coins to pay the mercenaries such as the stunning Gold Dukat, Struck by mintmaster Thomas Beheim which comes to auction at SGB this month. Chalices crosses, and other sacred items were sacrificed to fund the defence of the city. This emergency coinage, known as "Siege Money", became a vital lifeline for the city’s survival. Without these funds, it would have been impossible to maintain the loyalty and morale of the mercenary forces, whose continued presence was crucial to holding off the Ottoman siege

This act of melting down religious treasures underscored the gravity of the situation. The decision to use sacred items for coinage was not taken lightly, as it risked provoking the ire of the Church and alienating the deeply religious citizens of Vienna. However, in the face of the Ottoman threat, there was little choice. The siege money became a symbol of Vienna’s determination to defend itself against overwhelming odds, even at the cost of its spiritual heritage.

Ottoman Tactics and Christian Resistance

Throughout the siege, the Ottomans employed a variety of tactics to break through Vienna’s defences. They used heavy artillery to bombard the city’s walls, launched direct assaults on key fortifications, and dug extensive tunnels in an attempt to undermine the city’s defences. The Ottomans were renowned for their expertise in siege warfare, and these techniques had proven successful in many previous campaigns

However, Vienna’s defenders were equally resourceful. Count Niklas Salm, and his commanders organised a robust defence, utilising the city’s limited manpower to maximum effect. Local militias, mercenaries, and civilians all played a role in holding off the Ottoman assaults. The city’s walls, though battered, held firm thanks to tireless repair efforts by the defenders.

Weather also played a significant role in the outcome of the siege. The Ottoman forces were not prepared for the harsh autumn weather of Central Europe, and the extended campaign took a toll on the morale and health of the troops. As the weeks wore on, the besieging forces struggled with supply shortages, disease, and exhaustion.

The End of the Siege and its Aftermath

By mid-October 1529, after several failed attempts to breach Vienna’s walls and with the onset of winter approaching, Suleiman made the decision to lift the siege. The Ottoman army had suffered significant losses, and with no breakthrough in sight, continuing the campaign was no longer feasible. Suleiman’s forces withdrew, marking the end of the siege.

Though the Ottomans had failed to capture Vienna, the siege had a profound impact on both sides. For the Ottomans, it was a rare setback in their otherwise successful expansion into Europe. However, the empire’s power remained formidable, and it would take several more decades before the Ottoman threat to Vienna was finally ended in 1683, during the Second Siege of Vienna

For the Holy Roman Empire and the defenders of Vienna, the siege was a symbolic victory that bolstered morale across Europe. The successful defence of the city became a rallying point for Christian forces, who saw it as a sign that Europe could withstand the might of the Ottoman Empire. The sacrifice of Vienna’s treasures to strike emergency coinage only added to the legend of the city’s resistance.

Lot 446: Austria, Holy Roman Empire, Ferdinand I (1521 ‐ 1564), gold Dukat Klippe, Siege of Vienna, 1529, Vienna mint, crowned and armoured bust, arabesques at cardinal points. Rev. Long cross pattée; in quarters coats ‐ of ‐ arms of Niederösterreich, Castile, Hungary, and Bohemia, arabesques at cardinal points, 3.54g (Fr. 22; Markl 278). Good Very Fine, slightly wavy flan, small dig in the field on obverse andminor hairlines to surfaces. Est £1,000 ‐ 1,500

For more information visit www.sgbaldwins.com or register to bid here